Evolving a Better Blackjack Strategy

Since writing my last evolutionary algorithm program, I have been looking around for other places where this strategy of optimization would be a good fit. The idea of having a population of objects that improves using the concepts of biology is not only fascinating, it is proven in the world around us. When I was getting ready for a trip to Atlantic City recently, I decided to brush up on my Blackjack in case I decided to gamble a bit while I was there. As it turns out, Blackjack strategies are a perfect candidate for an evolutionary program to evolve. There are 32 basic hands a player can have and 10 different hands the dealer can have, and a Blackjack strategy is a table of actions that the player should take given a combination of your hand and the dealer’s hand. This means that there are 4^320 different strategies possible, or 4.562×10^192 combinations. I pity the gambler that ties up their computer for a month trying to brute force the best strategy.

Update, May 2017: while the number of strategies is that high, figuring out an optimal strategy should not require these algorithms. Each cell in the table is independent; therefore simulations can be run per cell to figure out an optimal strategy, saving a ton of processing over simulating the entire table. The methods discussed in this article are still all correct and relevant, it is just not the most effective way to solve this problem.

The Program

Link to source code: https://github.com/Carrigan/EvolutionaryBlackjack.

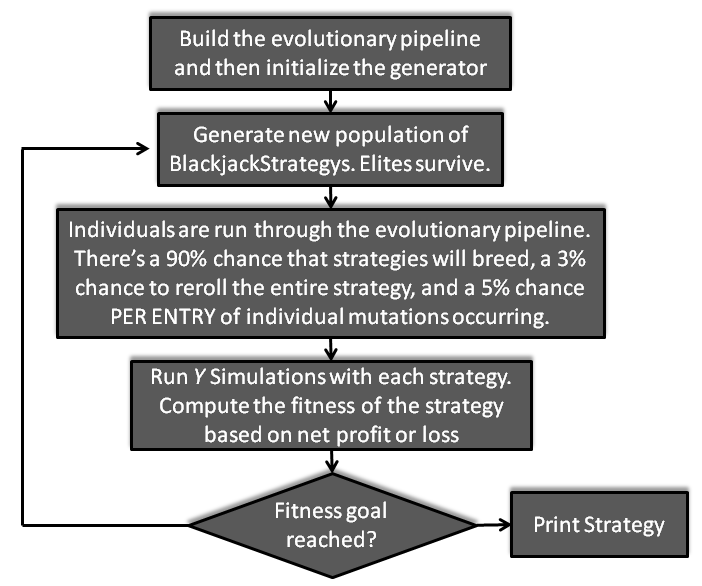

Like the last program I wrote, this program uses the Watchmaker Java library. This library is a very simple to use abstract evolutionary engine that enables evolutionary algorithms to be performed on any object. Below is a graphic depicting how the program works. Please note that the numbers involved were chosen for how you would typically run this program- they could be changed to produce more random or precise populations:

The most challenging part of writing an evolutionary algorithm is deciding whether a given principle of evolution can help your application or harm it. Introducing certain concepts will increase the randomness of your program and lead to a much more varied population. Examples of these concepts include mutations and crossover. In the real world we know that this is useful because diversity allows plants and animals to thrive in many different environments. On the flipside, some other concepts make a program focus in on beneficial genes. Examples of this include more aggressive selection strategies for crossover operations and elitism. While these functions may promote healthy genes, they also could lead to the program getting stuck in local maximums, and you should be careful when selecting which ones to use in a given application.

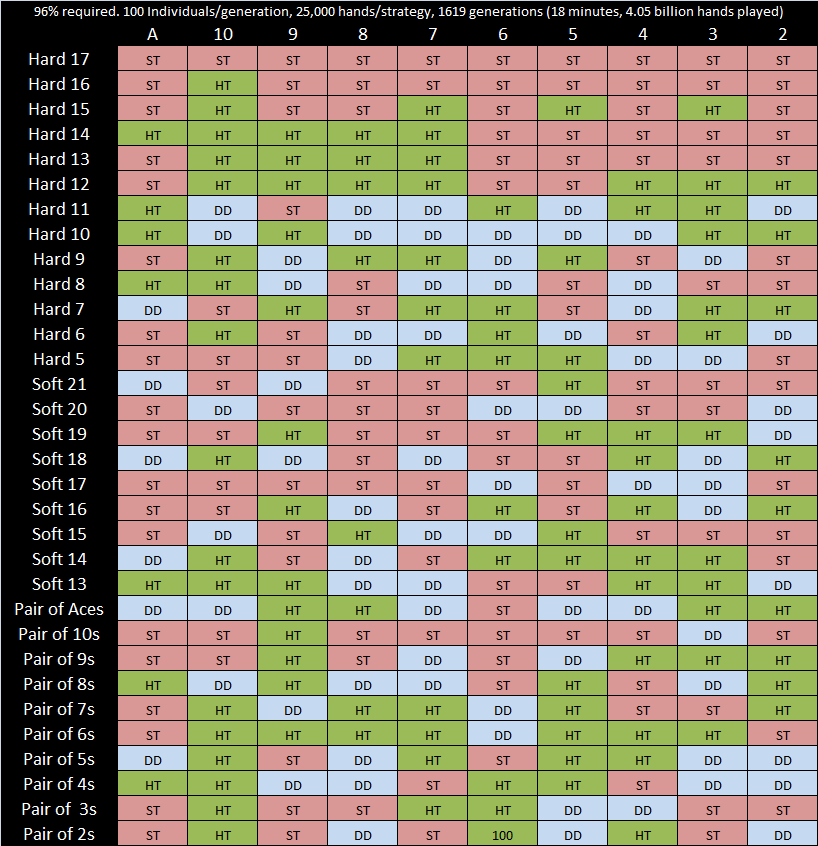

So how do you evolve a Blackjack strategy? Well first, you make it into an object. Just like the blackjack strategies you would find online, my strategy object was essentially a 32×10 grid of the four actions you can perform in blackjack: hit, stay, double down, and split. In order to evaluate a given strategy, the program plays a certain number of hands of blackjack, which the user decides. This number is extremely imporant. If it is too low, i.e. ten hands, then a strategy composed of pure garbage might double the players money with some luck. If it is too high, it will be extremely accurate, but if there are 100 individuals in a given population playing 1,000,000 hands per strategy, each generation of strategies will require 100 million simulated hands of blackjack. Today’s computers are pretty damn fast, but I don’t feel like waiting a week to get an answer of how to play blackjack.

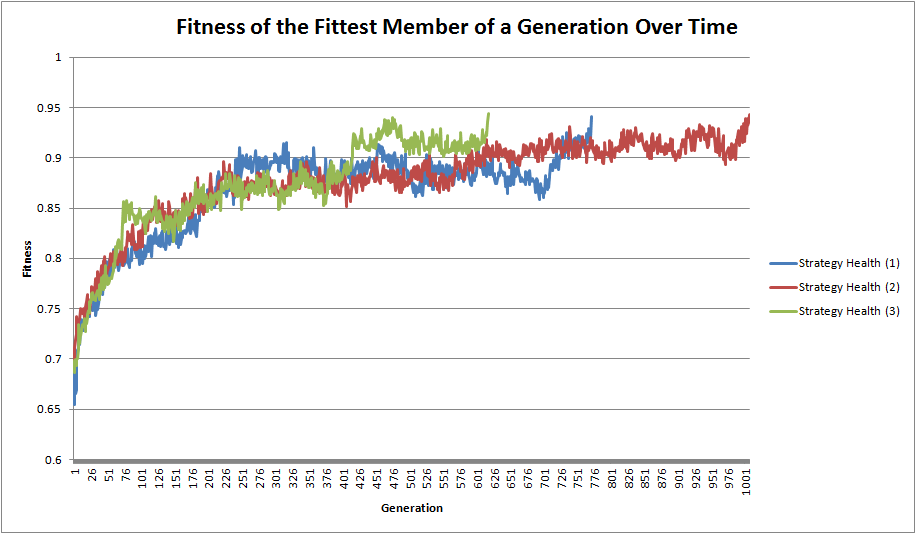

Time to talk about fitness. Not the type that comes with New Years resolutions, but in terms of a function that can be used to evaluate a member of the population. The fitness of a strategy here is calculated by dividing the amount of money the player has at the end of the simulation by how much they had at the beginning. For example, if the program starts with 100,000 and ends with 110,000, then its fitness will be 1.1. Spoiler alert: even the best strategies lost tons of money over the course of thousands of hands.

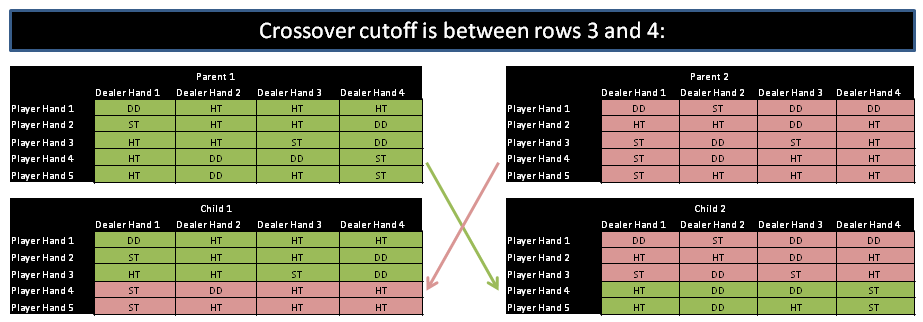

Next, I wrote several functions to perform mutations and crossovers. The crossover function created for this application works by taking two strategies, selecting a row (Player Strategy) to perform the crossover, and then creating two offspring with the upper rows of the two parents intact but the bottom rows switched. The graphic below depicts this operation on two 5×4 strategies:

Mutation is much easier to understand without a graphic. During Mutation, each cell of the strategy is iterated through and there is a small chance (5% in the code on Github) that a given cell will mutate. When a cell mutates, it changes at random to another action. There is also a chance (3% in the code on Github) that the entire strategy will randomize. If these chances are tweaked to be too high, then the program is roo random and will never settle at an answer. If they are too low, you risk falling into a local maximum. A lot of the literature on genetic algorithms covers how you know if your probabilities are too high or too low, or you can just play and tweak until you get a decent outcome.

Finally, the program must know when to stop. Below is a list of termination conditions that Watchmaker supports, along with how they work. I set the bar high here and required a TargetFitness of 96% to terminate this program. It’s not winning the big bucks, but it also isn’t coming home broke.

- ElapsedTime - Evolution will stop after X milliseconds.

- GenerationCount - Evolution will stop after X generations.

- Stagnation - Evolution will stop if X generations have not shown any improvement in the fittest individual.

- TargetFitness - Evolution will stop once the fitness of an individual in the generation

- UserAbort - Evolution will stop once the abort() function is invoked. Useful for a GUI program.

Conclusion

In the end, this program generated strategies that were very close to the strategies that you would find online. There were a few discrepancies between them, however, which I would like to talk about:

- Most importantly, I did not want to invest the time to write the code for splitting the cards. The framework is in place if someone wants to pick this up and implement it, but for a side experiment I was quite happy without investing the extra time it would take to add this feature. Thus, the results only allowed for standing, hitting, and doubling down.

- The program is written to allow for different actions to be taken for a pair of cards over the hard equivalent of the pair (i.e. a pair of 8s will be treated differently than hard 16 for splitting purposes). Since split was never implemented, this actually hurts the program since we WANT to treat a pair of 8s like a hard 16. A pair of 8s (1 in every 169 hands) does not occur as often as a hard 16, and therefore it’s strategy may not evolve as much.

- Due to the nature of this simulator, some of the results do not make sense because not enough hands could be played. For instance, if you set the simulator for 10,000 hands and the simulation only deals a certain situation (such as the player having hard 13 when the dealer is showing a ten) ten times, a poor strategy could get lucky with a small enough sample to look like a desirable gene. This could mess up generations to come. The way to overcome this is by playing larger amounts of hands, but this takes much longer.

That being said, the results are pretty good. In general, you want to stay at a lot of the higher hands, double down right around a hand of 10, and hit everywhere else (I use this strategy personally). In the two solutions that this program computed below, you see this pattern quite a bit.

Examples of good strategies generated by this program. Click for a better image. The fitnesses of the populations over time follow a pattern typical of evolutionary algorithms. The best way to describe this would be a horizontal asymptote (the theoretical maximum fitness) being approached by a very noisy exponential curve. Three instances of the program running with the same parameters are shown below. The number of generations necessary fluctuates quite a bit here, common with genetic algorithms.

Fitness goal: 94%. 100 Individuals, 25,000 hands per strategy.

I may work on this project a bit more in the future (by adding splits), but for now I would be quite happy coming back from Atlantic City with 96% of the money I went with. Good luck!